Authentication and authorization in a microservice architecture: Part 6 - implementing complex authorization using Oso Cloud local authorization

application architecture architecting security microservice architecture implementing queriesContact me for information about consulting and training at your company.

The MEAP for Microservices Patterns 2nd edition is now available

This article is the sixth in a series of articles about authentication and authorization in a microservice architecture. The complete series is:

-

Overview of authentication and authorization in a microservice architecture

-

Implementing complex authorization using Oso Cloud local authorization

In the previous article, I described how a microservices-based application can use an authorization service, such as Oso Cloud, to make authorization decisions.

Once the application’s authorization policy is defined declaratively in Oso, the application populates Oso with facts which correspond to relationships between entities.

Then, when handling a request, such as disarmSecuritySystem(), the Security System Service invokes Oso passing the user’s identity, the operation to authorize (“disarm”), and the security system ID.

Oso decides whether the operation is authorized by evaluating the authorization policy using its stored facts and the authorization request’s parameters.

This approach works well for operations that act on a single entity. Potentially complicated authorization logic is replaced by much simpler calls to Oso Cloud. But invoking Oso repeatedly for bulk operations that act on large collections of entities is likely to be inefficient due to the communication overhead. This article starts by exploring a more efficient way to authorize bulk query operations using a combination of local facts and facts stored in Oso Cloud. After that, it revisits how to authorize single-entity operations using locally stored facts. Let’s begin by looking at a simple example of a bulk query operation.

Problem: Implementing findSecuritySystems()

The findSecuritySystems() system operation returns a list of the security systems that the user is authorized to access.

This data is used to populate the View Security Systems page of the RealGuardIO application’s UI.

Let’s first look at why such a bulk query is challenging to implement.

Inefficient approach: One-by-one authorization using Oso

One way to implement authorization for findSecuritySystems() to do the following:

-

Query the database for all security systems - the

Security System Servicedoesn’t maintain any other authorization-related data -

For each security system, query Oso to check whether the user is authorized to view that security system

This approach is straightforward to implement.

The problem is that unless there are just a few SecuritySystems, it’s likely to be inefficient.

A better approach, which was described in part 1, is to integrate the authorization check into the data access logic, i.e. the SQL query.

In part 4 I described this approach with an example that efficiently retrieved SecuritySystems by executing SQL SELECT that joined the security_systems table with data replicated from the Customer Service.

Let’s look at how to do that when using Oso Cloud.

Integrating Oso into the database access logic using local authorization

Oso Cloud has a feature called local authorization, which makes authorization decisions using a combination of facts stored in Oso Cloud and the service’s database.

Two key local authorization methods are oso.listLocal() and oso.authorizeLocal().

The oso.authorizeLocal() method is the local authorization equivalent of oso.authorize().

It returns a SQL SELECT statement that, when executed by the service, returns either true (authorized) or false (not authorized).

The oso.listLocal() method returns a SQL WHERE clause fragment that can be used to implement bulk queries such as findSecuritySystems().

I’ll describe how to use oso.authorizeLocal() later in this article.

Let’s first look at how to use oso.listLocal().

Configuring local authorization

To use local authorization, you must specify a local_authorization_config.yaml when creating the Oso client:

public class OsoServiceConfiguration {

String configurationFilePath = ...;

@Bean

public Oso oso(@Value("${oso.url}") String osoUrl,

@Value("${oso.auth}") String osoAuth) {

var optionsBuilder = new OsoClientOptions.Builder();

if (configurationFilePath != null) {

optionsBuilder.withDataBindingsPath(configurationFilePath);

}

return new Oso(osoAuth, URI.create(osoUrl), optionsBuilder.build());

}

The path to the configuration file is passed to optionsBuilder.withDataBindingsPath().

One interesting challenge in a Spring Boot application is that the configuration file is typically in a JAR file nested within the Spring Boot JAR file.

The RealGuardIO example application contains a ClasspathLocalAuthorizationConfigFileSupplier that maps a classpath resource to a java.nio.file.Path using a Virtual FileSystem - a Java feature that I was previously unaware of.

The local authorization configuration file contains two sections.

First, the first section maps Polar predicates, such as has_relation(…), which are named logical rules or facts in Oso Cloud’s policy language, to SQL SELECT queries.

This mapping enables Oso Cloud to generate SQL that uses facts stored locally.

Second, the second section maps resource types to database column types.

This section is optional but recommended in order to improve performance.

Interestingly, in this particular example, all required authorization data is replicated to Oso, so no fact mappings are required.

Strictly speaking, this example can use Oso.list() instead of local authorization.

Oso.list(user, permission, resourceType) returns a list of resourceIDs that the user has permission to perform an action on.

A service can then use that list to construct an SQL SELECT.

However, oso.listLocal() is not only more convenient, since it returns a SQL fragment, but it also supports scenarios, such as the one described later in this article, that require local data.

Here’s the configuration file that configures local authorization:

facts:

sql_types:

Location: integer

SecuritySystem: integer

This configuration file specifies that Locations and SecuritySystems have an Integer primary key.

Later in this article, we will revisit this configuration file for a scenario where some facts are stored locally.

Implementing findSecuritySystems() with oso.listLocal()

Let’s now look at how findSecuritySystems() can use oso.listLocal().

The listLocal() method has four parameters:

-

user- the ID of the user attempting to access the resources -

permission- the permission, such asview -

resourceType-SecuritySystem -

ID column- the primary key column of the table containingSecuritySystems

This method makes it straightforward to integrate authorization checks into SQL queries.

The SQL SELECT for retrieving SecuritySystems looks something like this:

var sql = "SELECT * FROM ss security_systems WHERE " + oso.listLocal(...);

The SELECT’s WHERE clause is simply the fragment returned by listLocal().

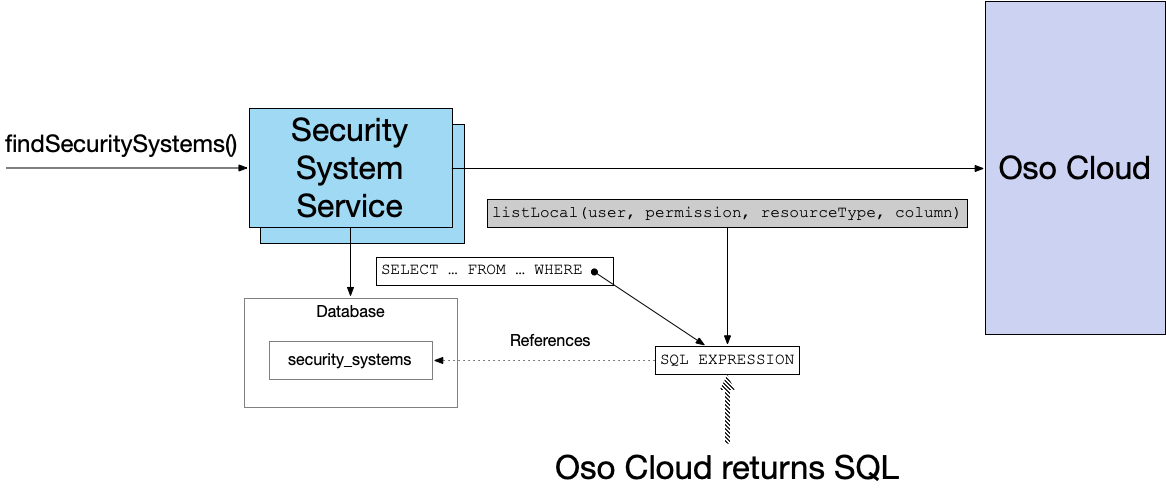

The following diagram shows how this works:

In this example scenario, listLocal() returns a SQL fragment that’s equivalent to ss.id IN (202, 203).

In other words, Oso Cloud returns an SQL WHERE-clause predicate containing inline values that constrain the IDs of the SecuritySystems that the user is allowed to view.

Later, you will see that the SQL predicate can join with other tables when authorization uses local data.

Let’s now look at an example of using local fact data for authorization.

Making authorization decisions with locally stored facts

Currently, the Customer Service and Security Service populate Oso with all the facts needed for authorization.

As a result, the SQL fragment returned by Oso.listLocal() does not reference any database tables.

However, while the Customer Service needs to publish its data to Oso so that it is available to the Security Service, the Security Service does not.

Instead, it can use local authorization to combine the facts in its database with those in Oso.

Specifically, the Security Service does not need to publish the SecuritySystemAssignedToLocation event to maintain the Location-SecuritySystem relationship in Oso.

Instead, the has_relation(SecuritySystem{…}, "location", Location{…) fact can be mapped to the SQL SELECT that queries the security_system table.

Let’s first look at the configuration file that defines the mapping.

After that, we’ll revisit the findSecuritySystems() query.

Finally, we’ll explore how to use oso.authorizeLocal().

The configuration file

Here’s the Oso configuration file that maps the has_relation(SecuritySystem{SECURITY_SYSTEM}, "location", Location{LOCATION}) relation to the security_system table:

facts:

"has_relation(SecuritySystem:_, String:location, Location:_)":

query: 'SELECT id, location_id FROM security_system WHERE location_id IS NOT NULL'

sql_types:

Location: integer

SecuritySystem: integer

Let’s now look at how this affects the SQL fragment returned by oso.listLocal().

The findSecuritySystems() query with local facts

While the code that implements findSecuritySystems() is unaffected by this change, the SQL fragment now references the security_system table.

Oso Cloud determines the locations that the user is authorized to access and returns an SQL fragment that queries the security_system table to determine the IDs of the SecuritySystems at those locations.

Here’s an example fragment:

ss.id IN (WITH RECURSIVE

c0(arg0, arg2) AS NOT MATERIALIZED (

SELECT id, location_id FROM security_system WHERE location_id IS NOT NULL

)

SELECT f1.arg0

FROM c0 AS f1, (

VALUES (1769998271122), (17699982711222)

) as cs( arg0 )

WHERE f1.arg2 = cs.arg0

)

This generated fragment uses common table expressions that are essentially named subqueries. It’s equivalent to:

ss.id IN (SELECT id FROM security_system WHERE location_id IN (1769998271122, 17699982711222))

Now that we’ve seen how to use oso.listLocal() to implement bulk queries, let’s look at local authorization for single-entity operations.

Using authorizeLocal()

Since some facts are only available locally, the Security System Service cannot use oso.authorize() (described previously in part 4) to authorize operations such as ‘arm’ and ‘disarm’.

Instead, it must use oso.authorizeLocal().

This method has three parameters:

-

user- the user attempting to perform the operation -

permission- the operation, such as “disarm” -

resourceID-SecuritySystemwith ID 101

It returns a SQL query that determines whether the user is authorized to access that resource.

The query returns true or false.

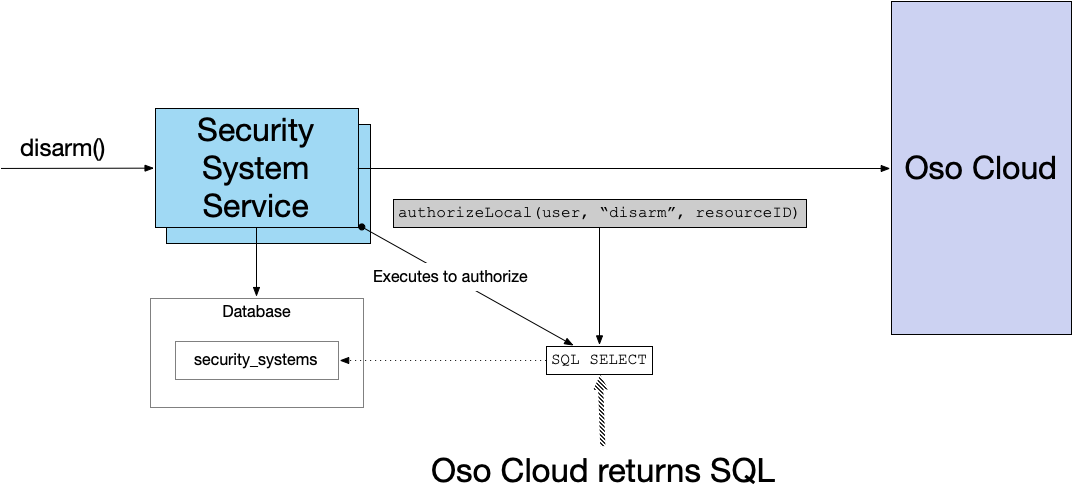

The following diagram shows how it works:

Here, for example, is how the Security System Service can check whether a user is authorized to disarm a security system:

var sql = oso.authorizeLocal(

new Value("CustomerEmployee", userId),

"disarm",

new Value("SecuritySystem", securitySystemId)

)

Boolean allowed = jdbcTemplate.queryForObject(sql, Boolean.class);

Here’s the SQL query returned by authorizeLocal():

WITH RECURSIVE

c0(arg0, arg2) AS NOT MATERIALIZED (

SELECT id, location_id FROM security_system WHERE location_id IS NOT NULL

)

SELECT EXISTS (SELECT 1

FROM c0 AS f0, (

VALUES (1767657091967), (17676570919672)

) as cs( arg0 )

WHERE f0.arg0 = 1 and f0.arg2 = cs.arg0

) as allowed

This query is equivalent to:

SELECT EXISTS (

SELECT 1 FROM security_system

WHERE id = 1 AND location_id IN (1767657091967, 17676570919672)

) AS allowed

In other words, Oso generates a SQL query that determines whether the specified SecuritySystem is at a location that the user is allowed to disarm.

Show me the code

The RealGuardIO application (work-in-progress) can be found in the following GitHub repository.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Hazal Mestci for reviewing this article and providing valuable feedback.

Summary

-

Oso local authorization enables a service to make authorization decisions using a combination of facts stored in Oso and the service’s local database

-

listLocal(user, permission, resourceType, ID column)- returns a SQL WHERE clause fragment that filters results based on permissions -

authorizeLocal(user, permission, resource)- returns a SQL SELECT that makes authorization decisions using local data

-

-

Local authorization requires a configuration file that maps Polar predicates facts, such as

has_relation, which are named logical rules or facts in Oso Cloud’s policy language, to SQL queries -

The generated SQL fragments and SELECT statements can include Oso facts, such as resource IDs

-

If local tables and Oso-stored data overlap, the generated SQL can contain a union of local and Oso-stored data

Need help with modernizing your architecture?

I help organizations modernize safely and avoid creating a modern legacy system — a new architecture with the same old problems. If you’re planning or struggling with a modernization effort, I can help.

Learn more about my modernization and architecture advisory work →

Premium content now available for paid subscribers at

Premium content now available for paid subscribers at